I’m always a little amazed at how much people pay monthly for TV service. We ran for years with no TV at all, and all the money we “saved” I easily spent on DVDs (and more I’m sure). Several year ago we decided that some amount of TV wasn’t a bad thing, it also gave me a great excuse to build a PVR based on MythTV. After shopping around StarChoice (now ShawDirect) seemed like the right fit. The basic package was cost effective and gave us enough TV. I liked the fact that we got HDTV in the base package, and that meant high definition hockey games and special events like the Olympics.

I’m always a little amazed at how much people pay monthly for TV service. We ran for years with no TV at all, and all the money we “saved” I easily spent on DVDs (and more I’m sure). Several year ago we decided that some amount of TV wasn’t a bad thing, it also gave me a great excuse to build a PVR based on MythTV. After shopping around StarChoice (now ShawDirect) seemed like the right fit. The basic package was cost effective and gave us enough TV. I liked the fact that we got HDTV in the base package, and that meant high definition hockey games and special events like the Olympics.

ShawDirect has a great policy (pdf) that lets you schedule seasonal breaks in service. I’ve been using one of those to try out using over the air (OTA) TV as our only source. We haven’t really noticed the lack of TV, even through the Stanley Cup finals (but our team wasn’t in it).

To move to OTA I needed two things: 1) a PC capture device for HDTV and 2) a set top box to convert the signal for use with my projector. The PC side of things came along as a deal from Dell – the Hauppauge WinTV HVR-950Q was on sale one day ($54.99). This came along with a tiny little antenna which surprisingly pulled several stations. The projector has no HDTV tuner (unlike most HDTV flat panel sets) and so it was off to eBay to get a set top box. This was the first time I had used the “Make an Offer” option on eBay and I was quite pleased with the price we negotiated. The tv tuner is known by several different brands: Centronics ZAT 502 HD / RTC DTA1100HD / Digiwave DTV5000HD.

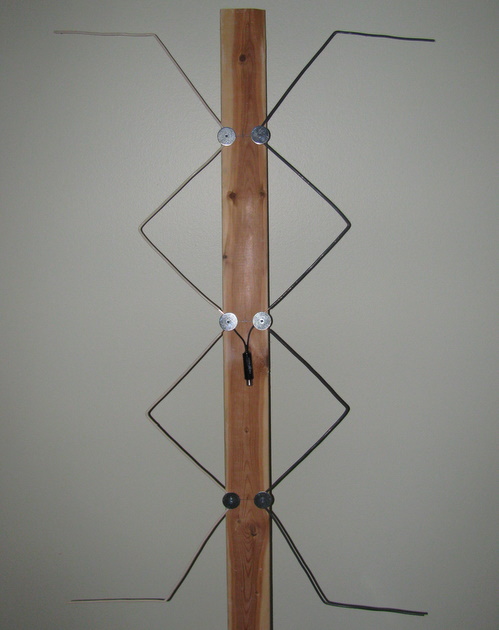

On the 2nd floor of the house I could easily pull in CBC to watch hockey using the dinky little antenna that came with the 950Q. To route the signal to the projector I needed to get a little creative and pull some RG6 from the attic to the basement, the MythTV box is also downstairs. In many situations almost anything will work as an antenna, and the simple bow-tie version I built with mostly stuff I had around already is pretty close to that.

My build was inspired by a write up I found using simple materials, the antenna I built is a Gray-Hoverman. I used a scrap of 1×3, some 14 gauge (2 conductor #14) electrical wire, some screws and fender washers. The only part I needed was a matching transformer. You can see the end result in the picture at the top of this post.

I have this antenna attic mounted, with 100ft of cable between it and the tv tuner. It works well, pulling in 5 HDTV stations all with little to no drop outs. I’d like to try to get PBS HD, but that may require a bigger antenna or an amplifier (a project for later).